Adapted from Trains Magazine 1969

A Railroader’s Dream

Imagine a Big Rock Candy Mountain railroad – an operating man’s dream – free from the burdens that typically plague American railroads. No terminal expenses, passenger train losses, damage claims, interchange delays, outdated work rules, excessive regulations, or obsolete equipment. Instead, this line would haul a single, captive, nonperishable, damage-free bulk commodity. It would operate continuously, pay crews by the hour, run loaded trains downhill and empties uphill, and never interchange with another railroad. No passengers, no classification yards, no highway crossings, and no ICC oversight.

It sounds idealistic, perhaps even illusory. But such a railroad existed – in Minnesota.

The Reserve Mining Company Railroad at a Glance (as of 1969)

- Length: 47 miles

- Locomotives: 21

- Ore Jennies: 990 (plus 9 cabooses)

- Commodity: Crude taconite only

- Route: From Babbitt to Silver Bay, Minnesota

- Grade: 0.6% against loads (1.5% against empties)

- Trains: Three-man, four-unit consists pulling 160-car, 18,430-ton trains

- Operating Authority: Private, not subject to ICC regulation

Built with a Singular Purpose

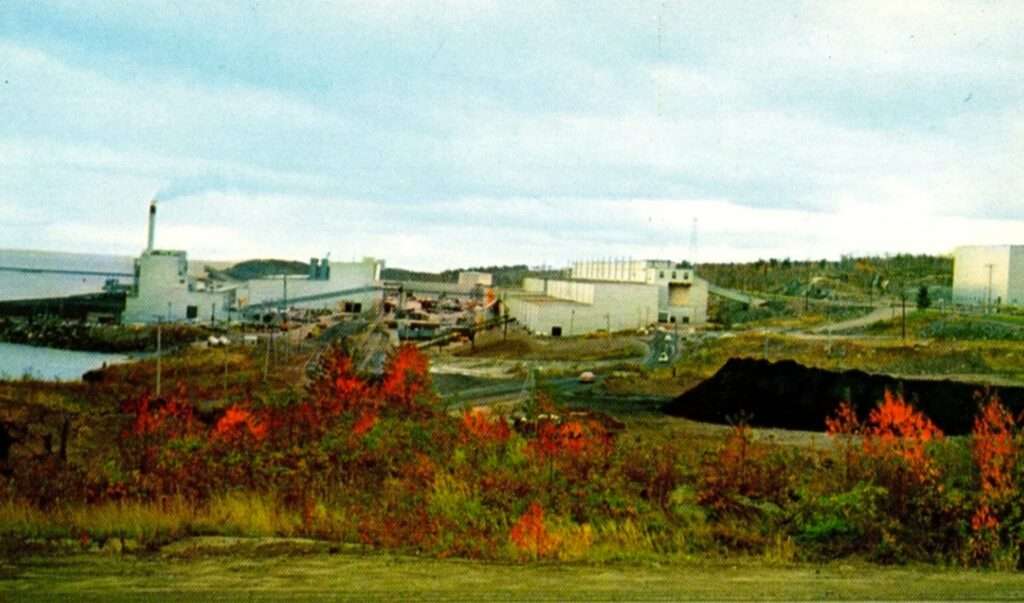

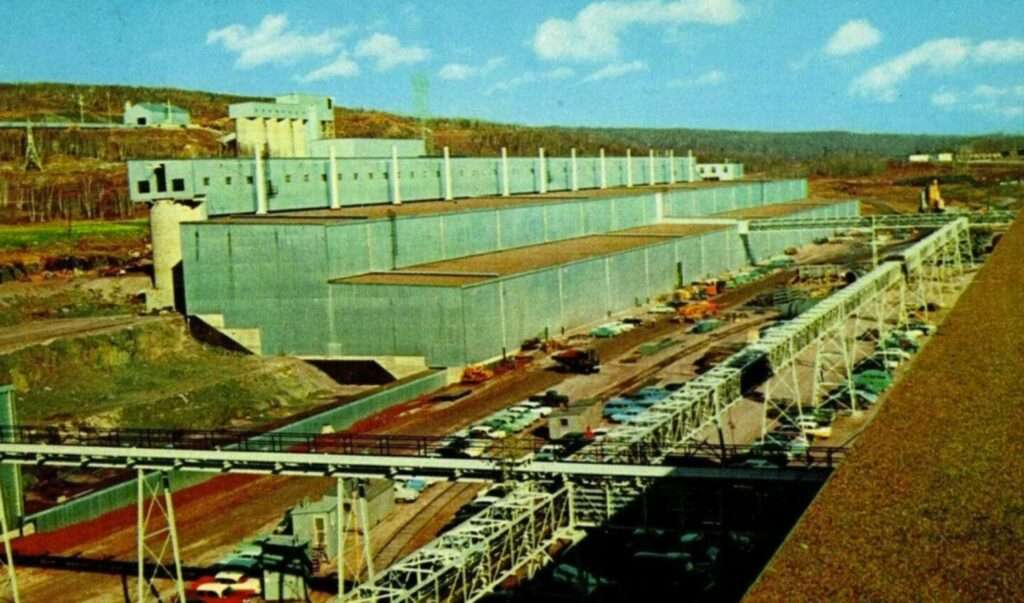

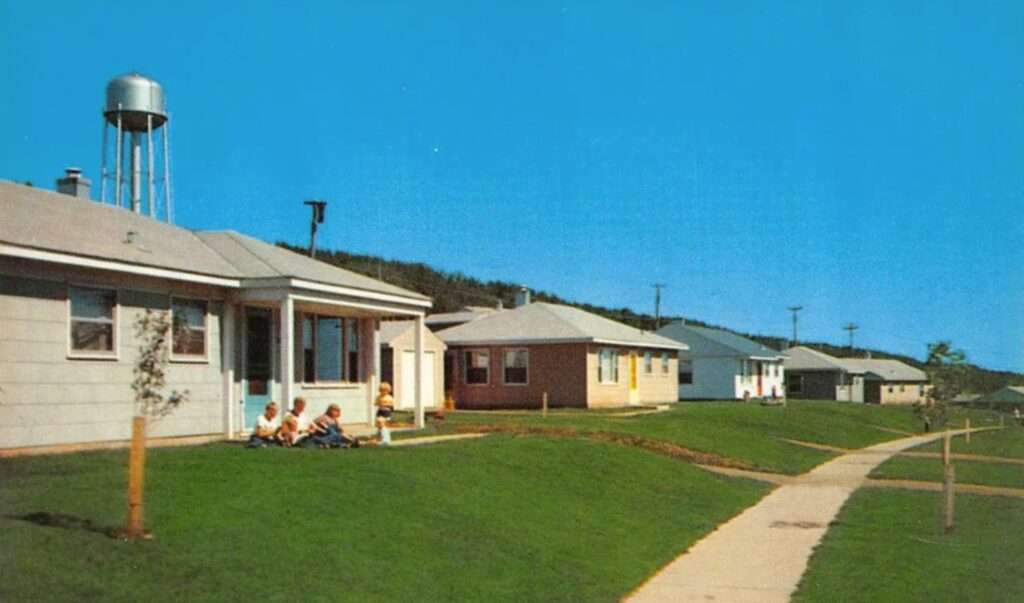

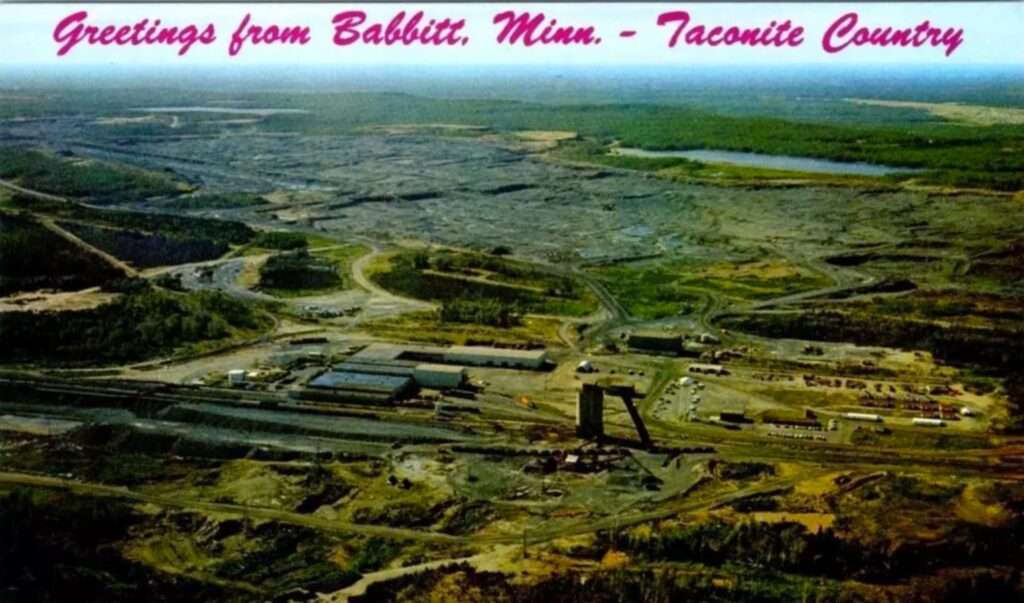

Constructed between 1953 and 1955, the Reserve Mining Railroad was designed as a vital link in a fully integrated taconite operation stretching from the ore-rich hills of northeastern Minnesota to the industrial cities of the Great Lakes. The line connected Babbitt, a company town founded in 1944 by Armco and Republic Steel, with Silver Bay, a purpose built port city on the North Shore of Lake Superior. Babbitt was strategically located near the eastern edge of the Mesabi Iron Range, where vast deposits of low-grade taconite could be mined using open-pit methods. The railroad enabled the efficient transport of raw taconite rock from the mine to the processing plant in Silver Bay. At the plant, the ore was crushed, concentrated using magnetic separation, rolled into pellets, and loaded onto lake freighters for shipment to steel mills in cities such as Cleveland, South Chicago, and Toledo. This seamless integration of mining, transportation, and shipping was a pioneering example of mid-century industrial planning. The very existence of both Babbitt and Silver Bay was rooted in this system, with each town carefully planned and constructed to fulfill a specific role in the taconite production chain. Together, they reflect one of the most ambitious and successful industrial developments in the history of Minnesota’s Iron Range.

While officially labeled an “intraplant railroad,” this was no ordinary industrial spur. Reserve’s line was engineered to high standards:

- Route: Skirting the south side of the Laurentian Divide through the Superior National and Finland State Forests

- Rail: 140-pound rail throughout

- North track: 39-foot jointed rail

- South track: 819-foot welded rail

- Ballast: 1½ inch crushed taconite for stability and drainage

- Signaling: Bidirectional signals on both tracks

- Crossovers: Power-operated, remotely controlled from Silver Bay, at mileposts 12½, 25, and 36

- Communications: Three fixed radio stations provided full coverage for engines, cabooses, Hy-Rail vehicles, and dispatchers

Rolling Stock and Power

Reserve’s equipment was tailored for efficiency and durability:

- Locomotives (as of 1969):

- 17 SD-series C-C units (for line-haul)

- 4 switchers (for terminal work)

- Ore Cars (1969):

- Built by ACF Industries

- 95-ton capacity

- 29 feet, 10 inches long

- Roller bearings and tightlock couplers

- Rotary couplers on Babbitt ends for unloading at Silver Bay

The company also operated nine cabooses, each built to withstand Reserve’s extreme environment. Caboose #17, now preserved at Caboose Falls, is one of these original nine. Used daily in the intense cycle of 160-car ore drags, its presence today offers a rare, firsthand glimpse at the workhorse equipment that made this operation so uniquely effective.

Train Operations

Each week, Reserve moved 8000 carloads of taconite, requiring 53 round trips of 160-car trains. Typical daily departure times from Babbitt were: 2 a.m., 5 a.m., 8 a.m., 11 a.m., 2 p.m., 5 p.m., 8 p.m., and 11 p.m.

- Locomotive ratings: 40 loaded cars or 45 empties per SD unit (non-winter)

- Speed limits:

- Loaded: 35 mph (30 mph downgrade)

- Empty: 40 mph

- Running times:

- Eastbound (loaded): 2 hours, 45 minutes

- Westbound (empty): 2 hours

The Workforce

Reserve operated with lean but specialized manpower:

- 40 in the Babbitt shop

- 35 in maintenance-of-way

- 4 in signal and radio maintenance

- 72 in train service

- Remaining employees in clerical and supervisory roles

Each train crew consisted of an engineer, a front brakeman, and a conductor. All workers were members of the United Steel Workers and were required to wear hard hats and safety glasses.

Environment and Appearance

The line crossed remote muskeg country with extreme seasonal temperature swings — from 100°F in summer to -45°F in winter. Locomotives were painted in the maroon and yellow colors of the Case Institute of Technology. The trains were utilitarian and uniform, broken only by the occasional local delivering fuel and supplies, or the rare outing of an ex-Great Northern parlor-observation car.

Leadership and Perspective

Rail superintendent George J. Sennhauser brought a wealth of experience to Reserve. A Purdue graduate and former Lima-Hamilton chief electrical engineer, he also served in C&O’s research department and as a night yardmaster in Chicago. Sennhauser’s mix of technical knowledge and operating experience made him uniquely suited to lead such a focused and demanding operation.

Performance Metrics

Despite its short length, Reserve’s railroad was a heavy hitter:

- Average daily mileage:

- Locomotives: 250+ miles

- Ore cars: 135 miles

- Notable milestone:

- SD9 units 1220 and 1222 surpassed 1 million miles in 13 years

Since 1964, the railroad hauled over 30 million tons of crude taconite annually, reaching 34.7 million tons in 1966. That’s:

- Comparable to all the bituminous coal moved yearly by the Louisville & Nashville

- 5x the tonnage of the Monon Railroad (541 miles long)

- Nearly 2x the Soo Line’s business (4692 miles long)

Though each ton only traveled 47 miles, Reserve still outpaces similar carriers. In 1966, Reserve recorded over 1.6 billion ton-miles – more than the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie’s 1.4 billion.

Cost Efficiency and Potential

Reserve didn’t disclose its cost data, as it operated at cost for its owners, Armco and Republic Steel. But with high tonnage, low grades, and tightly controlled operations, its performance likely exceeded that of even the lakeboats it fed.

The system’s design showed untapped potential. With expanded terminals and additional locomotives, it could have handled 70 million tons annually. Or – in an urban transit analogy – the same infrastructure could have supported 12-car passenger trains every 30 minutes, carrying up to 300,000 passengers per day.

A Hidden Gem of Railroading

Because of its isolation and industrial purpose, Reserve’s railroad remained largely unknown. Yet, it represented railroading at its most efficient and unencumbered – a textbook example of the mechanical genius Robert S. Henry once celebrated.

Reserve Mining’s rail department was far more than a conveyor of rock. It was, in every respect, a model railroad – a functional marvel tucked away in northern Minnesota, running quietly but powerfully between Babbitt and Silver Bay.